UK retailers have been taking a caning recently, on three main fears:

- Online taking market share: a natural fear, but omni-channel retail is the current vogue and this is hardly anything new.

- UK inflationary pressures: this is clearly a risk with many retailers, notably restaurants, seeing labour both as a major pressure on costs and a risk to sales as disposable income declines.

- UK recession fears: if inflation continues, a recession looks quite likely.

Yet at a recent conference on value investing, two of the presenters – both UK fund managers – recommended deep-value, bombed-out retailers. Nick Kirrage, co-head of value at Schroders, recommended Currys (CURY), while Edward Blain of Orbis recommended discount retailer B&M European Value (BME).

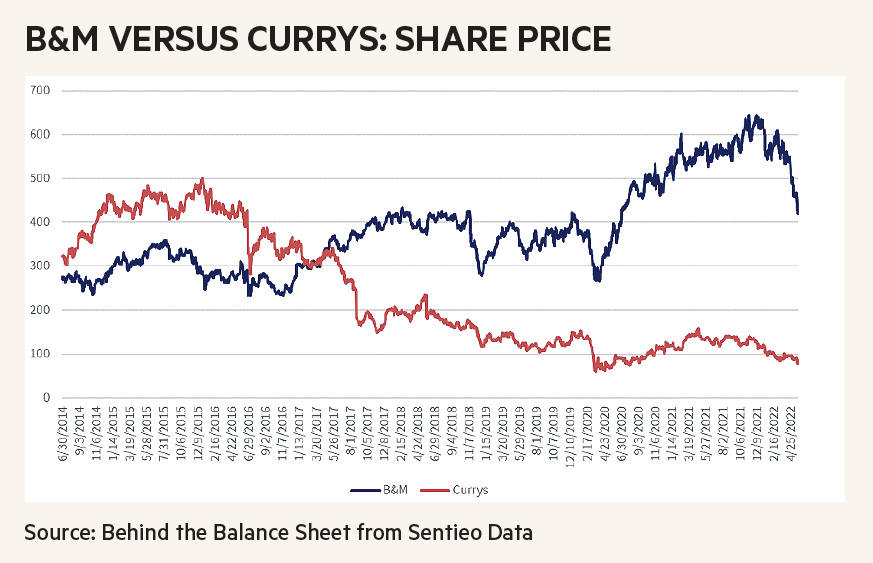

B&M is down 35 per cent from its high, while Currys is down 84 per cent from its peak and 49 per cent from its 2021 high (at the time of writing). The chart above dates from B&M’s float and shows that B&M has been a growth story while Currys has not. Currys has changed its name several times – it used to be Dixons – and the name change is designed to disguise a torrid past. The stock peaked at £5 in 2015, after what proved to be a terrible merger with Carphone Warehouse. Watch out for successful founders selling out!

The businesses

IC readers should be familiar with both companies. Currys is an electrical retailer, also trading under the PC World brand, offering a wide range of products from washing machines and similar white goods to PCs and phones, via all manner of products from the likes of Dyson and Apple.

It’s where I go when I need a new laptop (value-hunters can often find older models discounted in store), and for almost everything else I go to John Lewis, but I am probably not a typical customer. I have never actually visited a B&M store (spoiler: wealthy, London-based analysts tend to visit discount retailers to do research rather than to shop), but it’s a typical dollar-value type discount store, often situated next to an Aldi or Lidl, offering a limited range of branded food products where they have bought surplus stock that Kelloggs et al have needed to dispose of, for whatever reason, and a changing range of products geared to the season – garden products in the spring, toys at Christmas. All cheap and cheerful.

This is a classic low-cost format store, with effective private-label sourcing. The smaller town centre stores place greater emphasis on groceries and fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs), while there is a wider range in out-of-town outlets.

Valuation

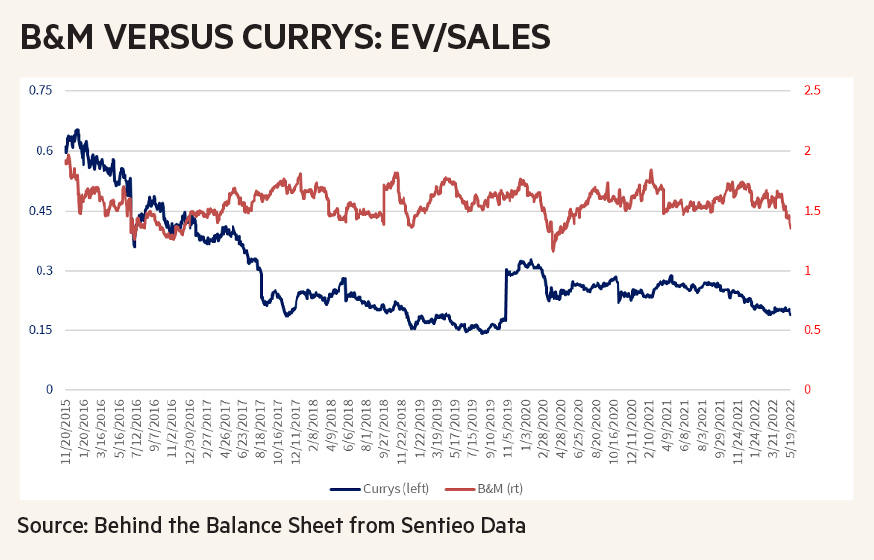

This is the key attraction of the stocks. B&M should benefit from shoppers trading down in more difficult times, even if its traditional customers are suffering. Currys will sell fewer big-ticket discretionary items and will have to be cheaper than peers. Given the uncertainty of earnings forecasts in the UK’s current economic circumstances, as well as the volatility of retail profitability, given high fixed costs, it’s much more sensible to use my favourite parameter of enterprise value (EV)/sales to value these businesses.

On Sentieo data, Currys is trading at 19 per cent of sales, which is lower than it was at the start of the pandemic, although the data suggests that it has traded even lower – I have not investigated. B&M is only 17 per cent above its pandemic low. These clearly are low valuations.

IFRS 16 distortion

The EVs are distorted in my view by the new-ish standard IFRS 16 which adds a notional debt to the balance sheet for the leased stores. I don’t believe that the standard is fit for purpose and the initial calculations companies made on introduction were subject to a significant degree of judgment. It’s therefore worth looking at the EVs in 'old money', again using the Sentieo data.

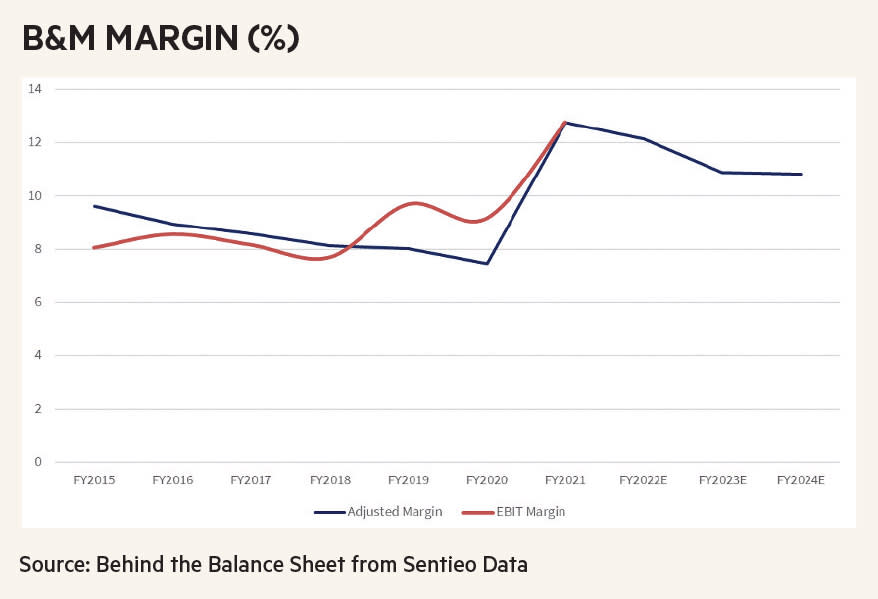

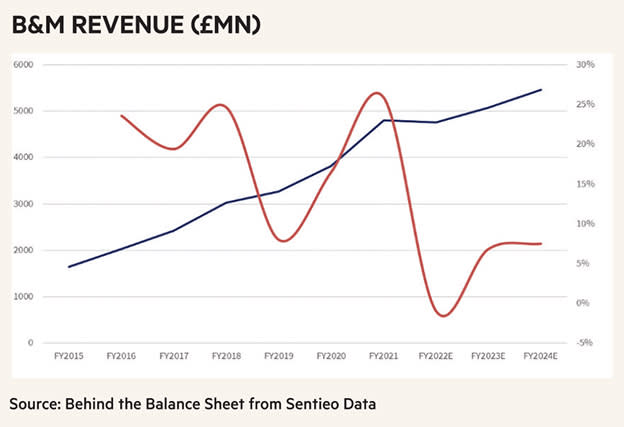

B&M has £1.3bn of notional debt on its balance sheet, which relates to the lease liabilities. Obviously, these liabilities are real, but relative to pre-IFRS 16, our EV/sales calculation is not like-for-like. I prefer to think of my EVs excluding this notional number – call me old-fashioned. These are 27 per cent of trailing revenues, so the EV on this basis would be 1.09 times sales. Margins have averaged 9 per cent and revenue growth has been strong – as shown in the charts above and below. The question on the valuation is less likely to be on revenue growth as the company should benefit from trading down and more one of the margin outlook.

Inflationary environments can pressure margins through the supply chain as it can take time for your input costs to feed through into sales prices. The 1970s was a very different environment, so it’s hard to draw analogies, but I am assuming many companies will see waves of margin pressure then expansion. There is no reason to expect B&M to be immune, but its ability to change product ranges should give it more flexibility and some element of protection.

For Currys, the numbers are even more dramatic. The 19 per cent of sales includes more than £1bn of notional lease liabilities, which are around 12 per cent of trailing revenues. So the EV/sales on a comparable basis is just 7 per cent. And this excludes £35mn of cash reserved for the insurance business (presumably extended warranties). That valuation really is a low number – it’s highly unusual to see a company with net cash trading below 10 per cent of sales, and it’s usually a buy. Spoiler: sometimes, though, they do go bust.

There is a simple investment case for B&M. It’s conceivable that it could continue growing even through a UK downturn. Although it is heavily represented in the north of England and less so in the more affluent south, it has fewer than 700 stores of the main format in the UK; there is an additional convenience store chain (Heron Foods, 300 stores) and a French business with just over 100. But there should be reasonable opportunity for further growth in store numbers. One risk is that the main driving force will be retiring but with a founder-led, family-owned business, succession risk will hopefully prove less of an issue.

The case for Currys is solely valuation. There are clear risks for the revenue growth and for margins, and in this area, Amazon (US:AMZN) is a formidable competitor. But at this valuation, it looks as if you are being paid to take the risk.

JPMorgan’s Investor Day highlighted “storm clouds on the horizon”, which is a great metaphor for current economic conditions. I chatted to a UK equity fund manager recently who has no retailers. He says that there are indeed storm clouds, and the market has probably over-egged the valuation de-rating, but we probably need to feel a few raindrops before people will buy these stocks – he suggested that a catalyst might be when the profit downgrades start to come through in reported numbers, then people can look at the upside.

I have always thought that it's impossible to second-guess when the market will start to focus on a particular issue. That’s why it’s helpful to take a long-term view and to resign yourself to being patient. It’s almost certainly early to look to buy the UK retailers, but Currys has such a low valuation that I can understand Nick Kirrage’s selection. B&M could well fall further, especially if it sees margin pressure, but the ultimate risk-reward looks interesting.