Brand loyalty is one of the great enigmas of business: it’s tricky to build, perhaps even more difficult to maintain, and it can be lost in an instant. For companies in the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector, to take just one example, it can also be the difference between outperforming their peer group and falling behind.

Loyalty to a brand-name product is inevitably tested during times of economic stress, when price inflation will lead consumers to seek cheaper alternatives. You’d expect this pattern, known as trading down, to be writ large across the income statements of firms such as Unilever (ULVR) and Haleon (HLN) in recent quarters. For the most part, this hasn't happened. And while the proportion of Unilever's business lines gaining market share has fallen from over 50 per cent to less than 38 per cent in the past two years – a sign that consumer staples businesses are not immune to shifts in consumer preference – its solution is to double down on its best products.

In the fourth quarter of last year, Unilever’s portfolio of 30 "power brands", on which its new management team is now concentrating, posted underlying sales growth of 6.5 per cent, while sales across the group were up 4.7 per cent. In short, the star cohort, which also accounts for around three-quarters of group turnover, collectively performed far better than the rest of the business. Haleon, for its part, has shown itself able to hike prices on some of its most recognisable products without harming sales volumes, another testament to the value of brand loyalty.

Details like these might lead investors to believe a portfolio packed with big-name labels is the secret to enduring success in FMCG. There is some truth to this, but that doesn’t mean that current leaders can defend their market share indefinitely. Beneath every power brand is at least a little innovation, a lot of marketing and, most important, the relatively fragile allegiance of everyday people.

The best medicine

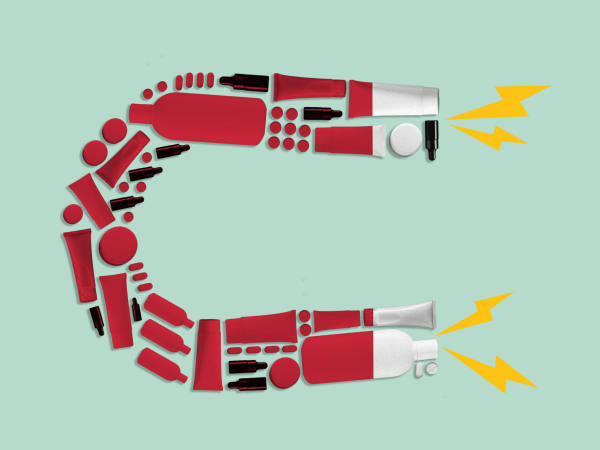

The problem with the “power brand” designation – used, effectively, as a shorthand for describing popular products with strong pricing power – is that some items are more magnetic than others, and the force of attraction can change over time. For instance, Unilever includes a number of recognisable ice cream brands in its portfolio of 30 high-growth products, but these struggled last year as consumers sought out cheaper alternatives.

On a February earnings call, chief executive Hein Schumacher said that “price elasticity in the in-home channel [was] much more negative than seen in other categories, with strong consumer down-trading to private label”. Customers were content to buy a supermarket’s own-brand “chocolate and vanilla cone” over the company's increasingly pricey, albeit iconic, Cornettos and Magnums.

Companies can invest in research and development (R&D) to help stave off categories' decline, as well as try to smooth out ups and downs by diversifying their business across several different brands. But the experience of the past two years suggests that limits will ultimately be reached if prices keep rising. However, in one particular sector, the bar is arguably higher.

Bruno Monteyne, an analyst with Bernstein Research, cites healthcare as the category where shoppers are least likely to trade down, even amid a cost of living squeeze. “Most products in the consumer world either have material downtrading risk (eg food), or cyclicality risk (eg sun cream),” he says. “Consumer health and pet food are exceptional in the sense that they don’t have those problems. Consumers protect those categories in their spending patterns much longer than any other.”

It’s well known that emotions drive many purchasing decisions (as opposed to cold financial logic). When parents are trying to ease a child’s flu symptoms, they probably aren’t as concerned about finding a bargain so much as a medicine perceived to be reliable and effective. “It’s human to care more about the medicine that you give to your kids than the choice of shoe polish or toilet cleaner,” Monteyne adds. “We are hardwired to massively care more about one than the other.”

This is not to say consumer health businesses are foolproof investments. Factors such as the vagaries of the cold and flu season and tough post-Covid comparatives can influence business – and shareholders' feelings – as much as underlying trends. Full-year results from Reckitt Benckiser (RKT) this week were a prime example of this kind of struggle.

Still, another reason Haleon and others with health-focused brands may not be as vulnerable to downtrading as Unilever, or even the likes of industry leader Procter & Gamble (US:PG), is that many of their products aren’t everyday staples in the purest sense. Ideally, people only need over-the-counter pain relief or cold medicine on occasion. This could mean they’re less likely to care about, or even notice, cost increases on popular brands such as Panadol and Advil.

Where Haleon does deal in daily necessities it does so with remarkable effectiveness. The group’s oral health division is its single-largest revenue contributor – netting 27 per cent of total sales in FY2022. Pain relief, by comparison, accounted for 23 per cent of turnover that year. Within oral health, just three brands are responsible for nearly 90 per cent of revenue: the Polident denture care range, the Parodontax gum care line and Sensodyne toothpaste and mouthwash.

The company has long boasted that the latter label is the global market leader in the treatment of dentine hypersensitivity, or sensitive teeth. It's a title that has been hard won through a combination of product innovation and consumer education. If a marketing guru were to draw up a foolproof guide to building a power brand, Sensodyne could serve as a perfect case study. The masterstroke here was not the development of a novel toothpaste formula, but the creation of a solution to a problem people didn’t know they had.

Sensodyne was invented in the early 1900s by a New York-based pharmacist called Alexander Block, who later founded the Block Drug Company. That firm, and its assets, were subsequently acquired by GSK (GSK) almost a century later. At the time, Sensodyne was a little-used product that was only available in pharmacies, despite dentine hypersensitivity being a known issue. Then GSK’s researchers made a discovery: most sufferers didn’t know the origin of their discomfort, or that it could be managed with the correct toothpaste.

Sales only took off after consumers started to understand that their pain was caused by exposure of the tooth’s dentine underlayer, which occurs when the gums and enamel are worn down. Until GSK’s marketing blitz began, most people had either attributed their pain to the stimulus that triggered it (ie a cold drink), or ignored it altogether. The company simultaneously marketed Sensodyne to dentists, who could recommend it to patients complaining of tooth sensitivity.

In many cases, consumers became aware that their symptoms indicated a dental condition and that there was a product to manage it in the same breath. In marketing terms, GSK had identified a significant unmet need in the general population – and was fortunate enough to have a product that could address it. But to keep growing sales, the company had to branch out into different geographies and expand its range of Sensodyne-label products. If an initial launch is the first phase of building a power brand, the steps that follow can solidify its status.

Innovation and expansion

“Companies like Reckitt and Haleon would say that they’re constantly innovating,” says Tineke Frikkee, head of UK equity research at Waverton Investment Management. “Private-label medicines are quite static in that these chemicals just do what they say they will in the body. But Reckitt might choose to add caffeine to a formula to give you a bit more energy, or incorporate a decongestant.” These add-ons help to differentiate products such as Reckitt’s Lemsip cold and flu capsules (at least in consumers' minds) from, say, a Tesco own-brand paracetamol tablet.

Haleon sells a Sensodyne toothpaste that also whitens teeth, as well as one that claims to resolve pain from dentine hypersensitivity within 60 seconds of application. “To maintain the pricing power of a brand, you need to keep communicating to the consumer,” says Bernstein’s Monteyne. “You need theatre on the shelves to engage with retailers and consumers. So you always need a steady flow of small-i innovation to keep having new packaging, new claims, new merchandising units.” But there is a risk of too much, as well as too little, innovation on this front.

Unlike pharmaceutical companies, consumer healthcare groups don’t have to engage in extensive (and expensive) R&D to bring products to market. However, ensuring shoppers are fully aware of latest releases doesn’t come cheap. It’s notoriously difficult to measure return on corporate marketing investments, although it is possible to assess what proportion of revenue is impacted by selling, general and administrative (SG&A) costs. These are all the expenses not directly attributable to making a product (ie they represent those tied to marketing and distribution).

At first glance, there doesn’t appear to be a huge degree of variation in the SG&A ratios of healthcare-focused FMCG groups. Both Reckitt and Kenvue (US:KVUE), the newly spun-off consumer health arm of Johnson & Johnson (US:JNJ), spend the equivalent of 35 per cent of their revenue on SG&A each year. Haleon’s average SG&A ratio across its last four financial years is much closer to 40. Brand power is so important that higher marketing spend is often viewed as a positive by investors, but the company is intent on bringing some of its costs down.

Chief financial officer Tobias Hestler told analysts last March that higher operating expenses are the legacy of the group’s connection to GSK. “We coped and cloned as much as we could in terms of processes. All our systems are a copy of what GSK had,” he said. “That had a huge benefit because it gave us stability [...] Now the price to pay is that these systems and processes probably aren’t fit for a consumer-type company.” He also promised SG&A spend would come down as the company matures.

From this, it’s possible to conclude that no single consumer health group is massively outdoing its peers in terms of marketing spend. Instead, variations in sales volumes can give a more pertinent clue to the effectiveness of marketing campaigns, and the underlying strength of brands. But financial heft is still important: RBC analysts think Reckitt has periodically struggled to get its products to resonate with consumers; the business's newly-appointed chief executive, Kris Licht, believes a doubling of R&D investment is the solution.

“This is particularly important given Reckitt’s exposure to the more 'science-y' categories in consumer staples land and its historical tendency to over-innovate – roll out and charge more for new products which offer little incremental benefit,” RBC says. In this sense, the company has fallen at the second hurdle for power branding: certain products underwhelmed because they didn’t address an unmet need.

Licht has also indicated that investment will be directed towards the company’s hygiene brands – a cohort that includes Dettol disinfectant and Finish dishwasher detergent, among others. The aim is to restore “product superiority” in the segment, as well as put greater resources into “brand equity” (ie marketing). Management has said these efforts will be self-funded through the reduction of the company’s fixed cost base, which has increased in recent years.

The focus on hygiene comes after an inevitable fall in sales volumes after the pandemic. Bernstein analysts say a “favourite bugbear” of theirs in recent years has been management’s use of consumer surveys that showed up to 90 per cent of people would hang onto their Covid-era hygiene habits. “When did consumers ever [accurately] tell us what they would do in the future?” they ask.

Towards the end of last year, it appeared Haleon was also contending with some volume struggles of its own amid destocking by retailers. The group’s third-quarter figures, released in November, showed volume growth slowing (but not falling). However, its power brands remained resilient, with Sensodyne, Paradontax, Theraflu and Centrum vitamins all seeing double-digit revenue growth. Full-year results will be released on 29 February.

Of course, much of the sales growth that FMCG companies, particularly in healthcare, have seen in recent years is down to price increases that have successfully been passed on to consumers. As inflation cools, investors are now putting more focus on volumes.

“Ultimately, margins improve if your sales grow faster than your costs,” says Waverton’s Frikkee. “But if your sales volume is staying at the same level, companies need to scale more. That means you need to gain market share in new countries, or expand into new distribution channels.” Defensive as the consumer health segment is, it is also becoming more competitive. Following the Kenvue and Haleon initial public offerings, French pharmaceutical giant Sanofi (FR:SAN) is reportedly planning to spin off its consumer-facing division in the coming years, although it’s not clear if this will be via a private buyout or an IPO.

“With the potential emergence of another listed consumer health business on the horizon [...] we expect investor interest in, and understanding of, the category to continue to grow,” said Barclays analysts in November. Incumbents such as Reckitt and Haleon may be forced to defend their share of certain markets more vigorously, and ensuring their brands remain relevant and accessible is paramount.

Holistic health

So where does this leave companies such as Unilever, which don’t deal in over-the-counter medicines? Do investors have to wait for cost of living pressures to ease before volume growth and market share gains resume in earnest? Unilever itself clearly understands the counter-cyclical value of consumer health. After all, it made no less than three bids for Haleon after GSK announced its intention to offload the business in 2022.

Shareholders and analysts were unimpressed by the approaches, with RBC stating that Unilever had too little experience with the clinical and medical characteristics of Haleon’s products. That has not, however, stopped the company from subsequently expanding into medically-adjacent categories, such as prestige beauty and wellness. At present, it has three brands in what is known as the “clinical derma-cosmetics” space – which are marketed as professional-grade products and sold at a premium price point.

This month, Barclays analysts also told investors not to underestimate the potential of Unilever’s upstart health & wellness unit. The business sells the electrolyte drink Liquid IV and a range of hair-growth supplements called Nutrafol, “both of which have the potential to become billionaire brands of the future”, according to the bank. The broker’s thesis is that health and wellness is evolving from a problem-and-solution-based industry to more of a standard FMCG category.

“Consumers are looking for holistic solutions for [...] mental, physical and emotional health and there is more interest in this category post-Covid, as self care and prevention has moved up the priority list," the analysts say. Regardless of whether these products end up on Unilever’s power brands list, or go on to take market share in their categories, the fact is that less 'science-y' consumer staples are more vulnerable to disruption. It’s difficult to prove that something like a multivitamin is working – at least in the way that a painkiller works – so much depends on public perception. The relative immaturity of these products might also mean consumers are more willing to try an alternative.

“The barriers to entry are very low with something like multivitamins,” says Frikkee. “You might gain a bit of market share, then someone else decides to repackage their product, or pay for a celebrity to promote it, and then their market share goes up.” All of which shows that trying to predict which company has the strongest range is hugely difficult. Building a brand is certainly more art than science, but science-backed products can have that defensive edge.