- Worries about inflation are yet to be quashed, as are concerns about the outlook for government bonds

- By contrast, can high-yield bonds carry on their hot streak?

The terms we use most can be telling, especially in the midst of a pandemic. "Unprecedented" did the rounds in 2020, while FTSE 100 bosses referred to "resilience" so often that the IC's Alex Newman was able to chart the frequency of its appearance against share price performance. Fast forward to late 2021, and the body behind the Oxford English Dictionary has opted for "vax" as its latest Word of the Year.

It’s a choice that says volumes about how far we have come in the pandemic. But if the world is slowly getting to grips with Covid-19, one potential Word of the Year for the investment community in 2021 points to a triumph of hope over reality.

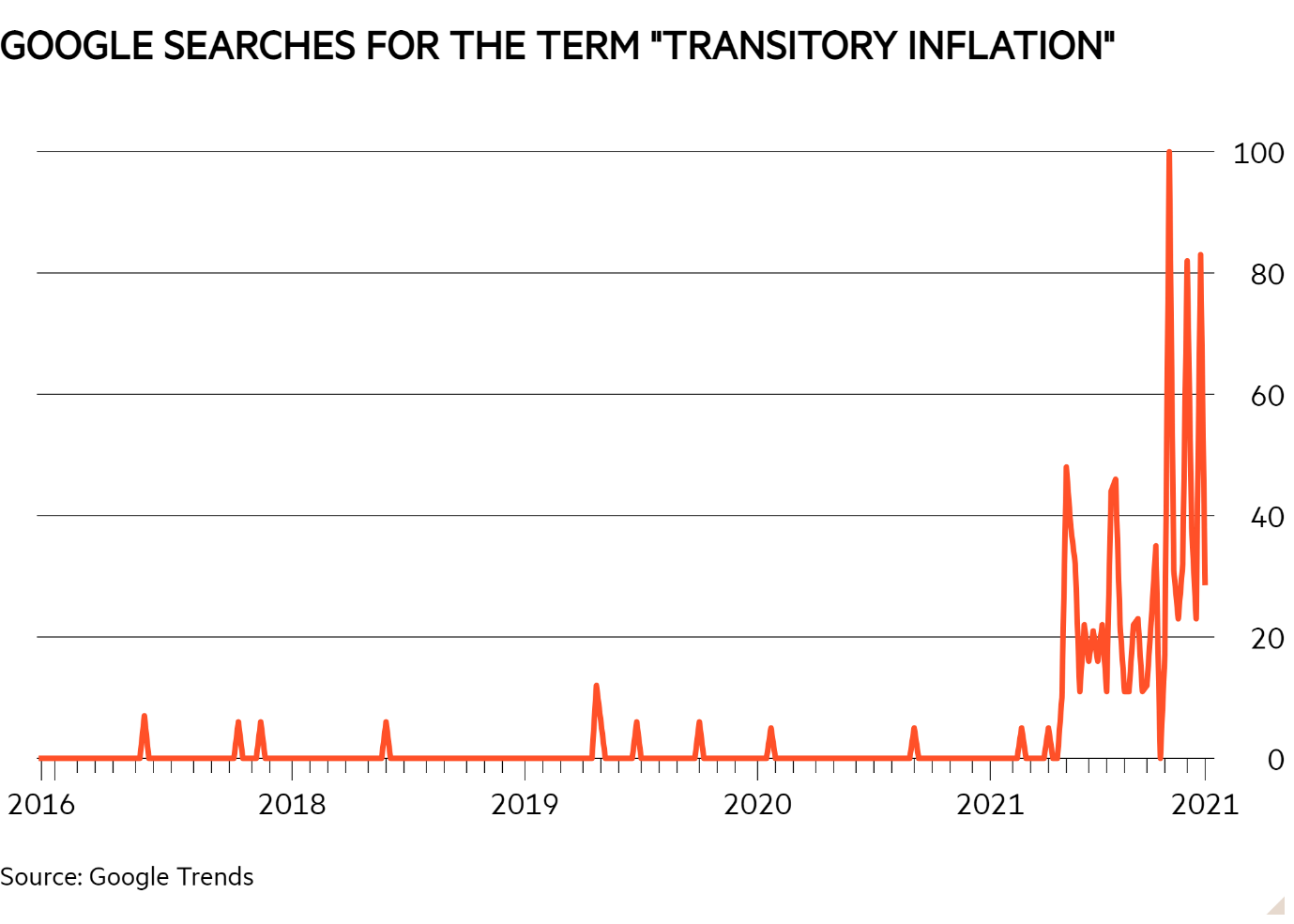

Andrew Eve, an investment specialist at M&G, is among those who think ‘transitory’ should top the charts for 2021 – and with good reason. Google searches for ‘transitory inflation’ have spiked this year, while investors and even some central bankers have confidently flown the ‘transitory’ flag for much of the year.

That stance has started to look precarious in the face of inflation hitting multi-year highs, and central banks now appear close to taking action even as they doggedly stick with their use of the word. In recent months, the talk has been of the Federal Reserve tapering its bond-buying programme, a move that could set the scene for interest rate rises when completed. Similarly, it was a bit of a surprise that the Bank of England held off from upping interest rates in November.

Several prominent bond fund managers, from Jupiter's Ariel Bezalel to Allianz Global Investors' Mike Riddell, have also been in the transitory camp, and it’s fixed-income investors who stand to lose out the most if high inflation persists. Firstly, it erodes the value of the fixed interest conventional bonds pay. Secondly, central banks do normally respond to inflation by tightening monetary policy, whether by raising interest rates or easing off on stimulus (as with tapering). That also spells bad news for bonds.

A big question mark

Imminent monetary tightening has become a big 'if', thanks to the Omicron coronavirus variant. At the time of writing speculation was rife that the Bank of England would duck a rate rise on 16 December, and if Omicron were to stymie economic activity that would make such action seem much less likely, boosting both government bonds and higher-quality investment-grade corporate bonds. 'Defensive' bonds such as these have sold off in line with rising inflation expectations, but tend to come back into favour when investors seek a safe haven. As Chris Iggo, chief investment officer for core investments at Axa Investment Managers, put it when news of the variant first emerged: “A new wave of lockdowns and falling activity would clearly push bond yields lower and delay the reckoning [for fixed income].”

But what is it that would really hurt the likes of government bonds? The current trajectory of monetary tightening in fact seems both modest and well-telegraphed. The Bank of England would be raising interest rates from an historic low of 0.1 per cent, likely at a gradual rate, while the US central bank has tended not to rush into rate hikes on the back of previous tapering efforts. As Salman Baig, a multi-asset investment manager at Unigestion, recently noted: “The Fed has largely shown cautiousness over the last few years, letting shifts in policy flow through and assessing the outcome before engaging further. Put another way, they tend to tap the brakes rather than slam their foot down.”

Iggo has stressed the need to consider what is already factored in to current prices. “Looking to 2022, investors need to contemplate a number of issues over the likely trajectory of inflation, whether central banks will need to do more than what is already priced in, and how portfolios should be adapted to hedge against a worse outcome,” he notes. “That worse outcome would be even higher inflation, a more aggressive tightening of monetary policies and a subsequent downgrade to growth prospects.”

Perhaps mindful of these risks, some of the biggest flexible bond funds tend to have relatively limited duration and quite varied exposures to government debt, as the chart on the left shows. And as we have previously noted (‘How bond funds are facing the inflation threat’, IC, 6 August 2021), the asset allocation disclosures on the Allianz fund, an outlier in the table, tend to give an overly simplistic view of what goes on in the portfolio, with activity including targeted use of derivatives and currency exposures based on economic conditions.

While those in the ‘transitory’ camp have come under pressure recently, the truth is the debate remains unresolved. Some argue that base effects (such as the collapsing oil price in 2020) help to boost inflation readings temporarily, while supply chain issues should fade away in time. They also tend to point to a variety of megatrends that can contain inflation, from globalisation to ageing populations and the deflationary impact of technology.

M&G’s Eve acknowledges these arguments, but notes that the low levels of inflation witnessed in the past four decades might in fact be an anomaly. For one, he suggests that the deflationary factors mentioned above could wane in influence. Globalisation could fall back in the face of rising nationalism and protectionism, ageing populations could shrink the workforce (driving up wage competition) and a pushback against the tech giants could reduce the sector’s clout. On top of that, several factors could push prices higher, from the rise of a younger electorate leading to “blunt policies aimed at redistributing wealth” to the persistence of accommodative fiscal policy and more structural drivers of inflation such as higher energy prices.

Investors should remember that index-linked bonds, which pay a variable rate of interest linked to inflation, do offer some refuge at a time of soaring prices. But they are a funny beast: because they often come with high levels of duration, index-linked bonds look vulnerable if interest rates rise.

Up the risk curve

Government bonds have had a rollercoaster ride this year, but riskier forms of corporate debt have racked up some impressive gains. The concerns about a possible rise in default rates we reported earlier this year have proved unfounded, while high-yield bond investors have seemed pretty unfazed by the prospect of inflation or interest rate rises. That said, the outlook seems less rosy from here.

In a world where high-yield bonds look expensive after a year of fat returns and the outlook seems less certain, caution may be warranted. Pierre Beniguel, a portfolio manager at bond specialist TwentyFour Asset Management, has put it starkly: “Fundamentally, the outlook for 2022 appears less supportive than it was 12 months ago. GDP growth is likely to slow and we expect underlying rates to gradually increase across established markets, a combination that typically leads to a pick-up in the default rate and a degree of credit spread widening.”

On a positive note he sees “pockets of value” and expects the number of bonds being upgraded to a higher credit rating to outweigh the downgrades. Likewise, he thinks the default rate will remain low, but expects returns in 2022 to depend on good bond selection and a focus on “smart defensive positioning” rather than chasing capital gains.

When it comes to bond subsectors with higher yields, there might be hope for emerging market debt. It has performed extremely poorly this year, not helped by the wobbles of China property giant Evergrande. However, some again suspect the US dollar will weaken over the next year. If this came to pass (always a big ‘if’), that would tend to be supportive of emerging market debt.

Product innovation

As in many aspects of life, the bond universe has been marked by a flood of environmental, social and governance (ESG)-compliant offerings in the past year. The government green bond market has come on notably this year, with several countries issuing such debt for the first time. This has gone down well: take the UK’s issue of a green gilt, the first £10bn of which was 10 times oversubscribed in September.

Popularity is a good problem to have, but more serious challenges have emerged. Kris Atkinson, who runs the Fidelity Sustainable Reduced Carbon Bond fund (LU2115357506), has warned that many hallmarks of a popular but immature sector have become evident. These include the 'greenium', where investors effectively pay up more for debt with an environmental sheen, or a recent lack of liquidity making it difficult to buy in. As with other areas of ESG, reporting standards need to improve, as does transparency. “Without more robust certification, the ‘green’ label still carries no guarantee of the use of proceeds and is more of a ‘trust me’ exercise,” Atkinson explains.

“Investors need to judge for themselves whether an issuer will actually use the funds for green investments and what impact that will have.

Atkinson notes that the “greenium” seems to have shrunk in parts of the corporate bond market, and perhaps the same will happen with government bonds. But as his comments suggest, thorough due diligence is a must for any investor eyeing up bond funds with a green or ESG remit. Finally, investors may question what kind of price premium they can tolerate both here and elsewhere. In the realm of other income products, the National Savings and Investments (NS&I) Green Savings Bonds unveiled in October have been widely criticised for offering just 0.65 per cent in interest, while also locking savers in for a three-year fixed term.